Is it the case that in Millais' painting that the young Raleigh is listening to a "Portuguese" sailor telling adventure stories of the "Spanish main"?

The southern portion of these coastal possessions were known as the Province of Tierra Firme, or the "Mainland province" in contrast to Spain's nearby island colonies.

For the Victorian audience for Millais at the Royal Academy in London in 1871, it came to epitomise the culture of heroic imperialism in late Victorian Britain and in British popular culture up to the mid-twentieth century. The foundation narrative of the British Empire required its own post-Columbus heroes, figures that included Raleigh and Drake, and, who, in the larger scheme of things, were those who were to capitalise this foundation with the proceeds of plunder rather than industry.

The Spanish main was their hunting ground, the Tudor monarchy a significant beneficiary of these spoils, and the English ambitions regarding colonisation and colonial exploitation should probably be seen to link Ireland and North America, as part of this foundational narrative.

The voyages of these Tudor adventurers was set against the backdrop of a globe that had been divided between the Spanish and the Portuguese. The world was so divided for nigh on 300 years after the voyages of Columbus

This division of the hemispheres of our planet took place by treaty in 1494, the Treaty of Tordesillas, signed only two years on from Columbus discovering islands in what we now know as the Caribbean. Columbus stubbornly assumed that the island of Cuba was "not an island", and that it was part of the mainland of east Asia, and he was never, in spite of the evidence of his own cartographer, completely persuaded that this was not the case.

The Treaty of Tordesillas , signed at Tordesillas in Spain on June 7, 1494, and authenticated at Setúbal, Portugal, divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between the Portuguese Empire and the Crown of Castile, along a meridian 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands, off the west coast of Africa. This line of demarcation was about halfway between the Cape Verde islands (already Portuguese) and the islands entered by Christopher Columbus on his first voyage (claimed for Castile and León), named in the treaty as Cipangu and Antilia (Cuba and Hispaniola).

The lands to the east would belong to Portugal and the lands to the west to Castile. The treaty was signed by Spain, 2 July 1494, and by Portugal, 5 September 1494. The other side of the world was divided a few decades later by the Treaty of Zaragoza, signed on 22 April 1529, which specified the antimeridian to the line of demarcation specified in the Treaty of Tordesillas. Originals of both treaties are kept at the General Archive of the Indies in Spain and at the Torre do Tombo National Archive in Portugal.

This treaty would be observed fairly well by Spain and Portugal, despite considerable ignorance as to the geography of the New World; however, it omitted all of the other European powers. Those countries generally ignored the treaty, particularly those that became Protestant after the Protestant Reformation, and it is to this that Millais' painting of the Boyhood of Raleigh is pointing to, just as as is the figure of a Portugese sailor represented pointing to the horizon.

The Treaty of Tordesillas

The treaty was included by UNESCO in 2007 in its Memory of the World Programme.

The naming of the Americas

The Spanish New World Empire

The Spanish main, in other words, was understood as being the Spanish New World Empire mainland that included the coasts of present-day Florida, the western shore of the Gulf of Mexico in Texas and Mexico, Central America and the north coast of South America. The term is most strongly associated with that stretch of the Caribbean coastline that runs from the ports of Porto Bello on the Isthmus of Darien in Panama, through Cartagena de Indias in New Granada, and Maracaibo to the Orinoco delta on the coast of Venezuela. Veracruz in New Spain was another major port.

So, it was along these coasts of the Spanish main that the first colonial settlements of the conquest were established, and most of them were destroyed or destroyed and refounded. In 1500 the city of Nueva Cádiz was founded on the island of Cubagua, Venezuela, followed by the founding of Santa Cruz by Alonso de Ojeda in present-day Guajira peninsula. Cumaná in Venezuela was the first permanent settlement founded by Europeans in the mainland Americas, in 1501 by Franciscan friars, but due to successful attacks by the indigenous people, it had to be refounded several times, until Diego Hernández de Serpa's foundation in 1569. The Spanish founded San Sebastian de Uraba in 1509 but abandoned it within the year. There is indirect evidence that the first permanent Spanish mainland settlement established in the Americas was Santa María la Antigua del Darién.

The first Conqistador?

Guesswork?

Martin Waldseemüller's Universalis Cosmographia, Waldseemüller's 1507 world map which was the first to show the Americas separate from Asia was sheer guesswork, backed up by logic. The name he used in this map for America seems to have stuck.

He was guessing that a logical global geography would mean that the continents of the "Americas" would, on their western coasts, look out to an ocean that separated the Americas from Asia. There are two different geographic theories contained in this single map. In the first theory, shown in the top left hand corner, he depicts a "gap" between the northern and southern continents.

In the second theory shown to the left of the portrait of Amerigo Vespucci at the top and centre of the map, he depicts an isthmus connecting the northern and southern landmasses.

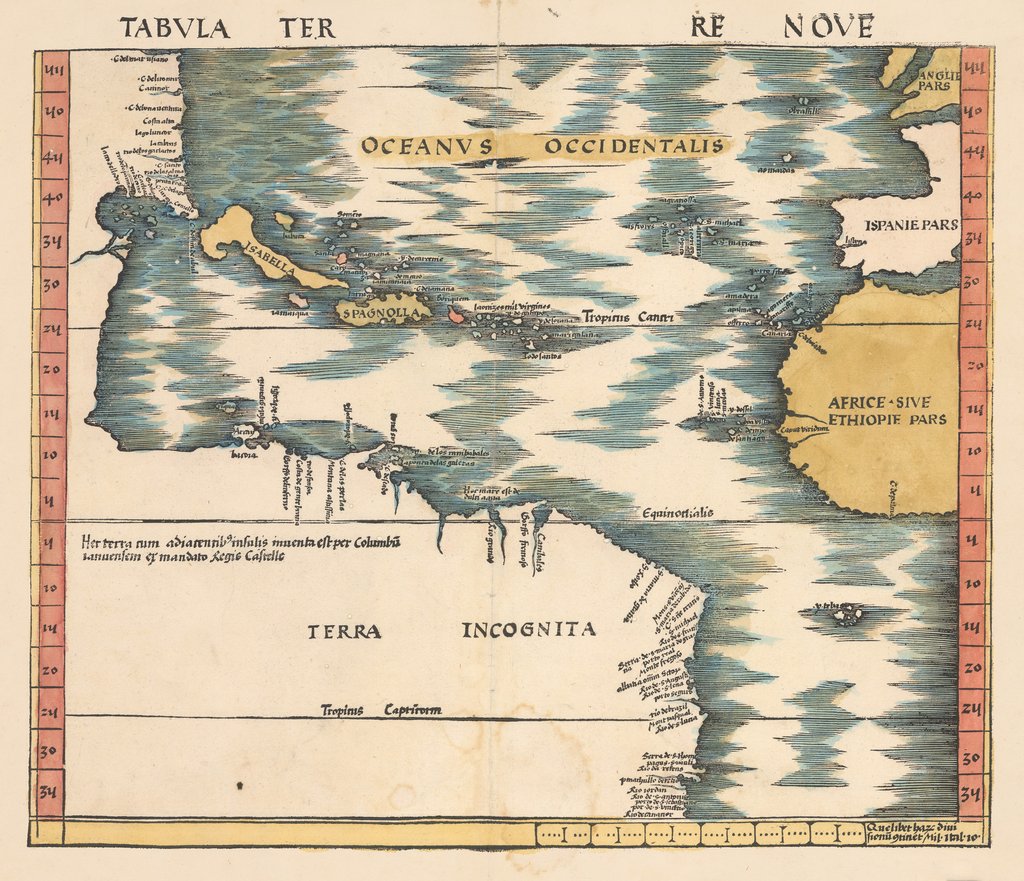

Some years later, Waldseemüller produced the earliest obtainable map to focus on the New World, otherwise known as the “Admiral’s Map,” for its reference to the “Admiral” as the source of the information in the text on the verso. The map originally appeared in a Ptolemaic atlas published out of Strasbourg in 1513.

Waldseemuller depicts the southeastern portion of present-day North America, connected to the northern portion of South America with a continuous coastline. At the time, this land connection was only a theory, waiting to be proven through further exploration. In the top left, we can see what appear to be the peninsula of Florida, and the Mississippi delta with several islands in between.

The massive “Terra Incognita” lacks any interior detail, but includes several place names and tributaries extending only a short distance inland. In the Caribbean, we find the islands of Isabella (Cuba), which was named after Queen Isabella of Spain, Spagnolla (Haiti & Dominican Republic), Borigeum (Puerto Rico), and Jamaiqua. The Archipelago within the same region represents the Bahamas, Turks and Caicos, Virgin Islands and some of the Lesser Antilles.

Western Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, and a portion of England appear in the right hand portion of the map. This map is of utmost importance to the cartographic history of the Americas. With the exception of the reduced version of this map published by Laurent Fries in 1522 / 1541, there would not be another map to focus on the Americas published until Ramusio’s map of 1534.

Jerry Brotton, in his A History of the World in Twelve Maps, points out that Waldseemuller has changed his mind regarding the naming of the "Spanish main" from the controversial "America" to "Terra Incognita".

This map clearly represents a contemporary knowledge, based on facts originating in the "discoveries" of Spanish mariners. There are no western coastlines. There is an eastern and northern coastline, and there are the names given to geographic features and settlements of, as yet, an unknown land.

Meanwhile in Veragua, and in the province of Tierra Firme . . .

In 1509, authority was granted to Alonso de Ojeda and Diego de Nicuesa to colonize the territories between the west side of the Gulf of Urabá and Cabo de la Vela, and Urabá westward to Cabo Gracias a Dios in present-day Honduras, and it was the westernmost portion that was given the name Tierra Firme.

Wishing to escape his creditors in Santo Domingo, Vasco Núñez de Balboa set sail as a stowaway, hiding inside a barrel together with his dog Leoncico, in the expedition commanded by the Alcalde Mayor of Nueva Andalucía, Martín Fernández de Enciso, whose mission it was to aid Alonso de Ojeda, his superior, to sail for the settlement at San Sebastian.

Balboa had arrived in the New World in 1500, motivated by his master after the news of Christopher Columbus's voyages to the New World became known. His first voyage to the Americas was on Rodrigo de Bastidas' expedition. Bastidas had a license to bring back treasure for the king and queen, while keeping four-fifths for himself, under a policy known as the quinto real, or "royal fifth". In 1501, he crossed the Caribbean coasts from the east of Panama, along the Colombian coast, through the Gulf of Urabá toward Cabo de la Vela. The expedition continued to explore the north east of South America, until they realized they did not have enough men and sailed to Hispaniola.

With his share of the earnings from this campaign, Balboa settled in Hispaniola in 1505, where he worked for several years as a planter and pig farmer. He was not successful and ended up in debt, leading to him to abandon life on the island and leave Hispaniola as a stowaway.

Meanwhile, Ojeda had already sailed from the coastal mainland for Hispaniola, leaving the colony under the supervision of the future conqueror of the Inca Empire, Francisco Pizarro, who, at that time, was only a soldier waiting for Enciso's expedition to arrive. Ojeda asked Pizarro to leave some men in the settlement for fifty days and, if no help arrived at the end of that time, to use all possible means to get back to Hispaniola.

Before the expedition arrived at San Sebastián de Urabá, Fernández de Enciso discovered Balboa aboard the ship, and threatened to leave him at the first uninhabited island they encountered; he later thought better of this and decided that Balboa's knowledge of that region, which he had explored eight years before, would be of great utility.

Pizarro had already started preparations for the return to Hispaniola, when Enciso's ship arrived. Following his discovery on board Balboa had gained some popularity among the crew because of his charisma and his knowledge of the region. By contrast Fernández de Enciso was not well liked by the men: many disapproved of his order to return to San Sebastián, especially after discovering, once they had arrived, that the settlement had been completely destroyed and that the natives were already waiting for them, leading to a series of relentless attacks.

Balboa suggested that the settlement of San Sebastián be moved to the region of Darién, to the west of the Gulf of Urabá, where the soil was more fertile and the natives presented less resistance. Fernández de Enciso gave serious consideration to this suggestion, and the regiment later went to Darién. However, the native cacique (chieftain) Cémaco had 500 warriors waiting, ready for battle. The Spanish, fearful of the large number of enemy combatants, made a vow to the Virgen de la Antigua, venerated in Seville, that they would name a settlement in the region after her should they prevail. It was a difficult battle for both sides, but the Spanish came out of the conflict as the victors. Cémaco, together with his warriors, abandoned their town and headed for the jungle. The Spanish plundered their houses and gathered a treasure-trove of golden ornaments.

Balboa kept the vow, and, in September 1510, founded the first permanent settlement on mainland American soil, and called it Santa María la Antigua del Darién.

Before long Balboa had, only by devious and and underhand means, become Governor of Veragua. With the title of governor came absolute authority in Santa María and all of Veragua. One of Balboa's first acts as governor was the trial of Fernández de Enciso, accused of usurping the governor's authority. Fernández de Enciso was sentenced to prison and his possessions were confiscated. However, he was to remain imprisoned only for a short time: Balboa set him free under the condition that he return immediately to Hispaniola and from there to Spain. With him on the same ship were two representatives from Balboa, who were to inform the colonial authorities of the situation, and request more men and supplies to continue the conquest of Veragua.

Balboa continued defeating various tribes and befriending others, exploring rivers, mountains, and sickly swamps, while always searching for gold and slaves and enlarging his territory. At the end of 1512 and the first months of 1513, he arrived in a region dominated by the cacique Careta, whom he easily defeated and then befriended. Careta was baptized and became one of Balboa's chief allies; he ensured the survival of the settlers by promising to supply the Spaniards with food. Balboa then proceeded on his journey, arriving in the lands of Careta's neighbour and rival, cacique Ponca, who fled to the mountains with his people, leaving his village open to the plundering of the Spaniards and Careta's men. Days later, the expedition arrived in the lands of cacique Comagre, fertile but reportedly dangerous terrain. However, Balboa was received peacefully and even invited to a feast in his honor; Comagre, like Careta, was then baptized.

Hearing about "the other sea"

It was in Comagre's lands that Balboa first heard of "the other sea." It started with a squabble among the Spaniards, unsatisfied by the meager amounts of gold they were being allotted. Comagre's eldest son, Panquiaco, angered by the Spaniards' avarice, knocked over the scales used to measure gold and exclaimed: "If you are so hungry for gold that you leave your lands to cause strife in those of others, I shall show you a province where you can quell this hunger". Panquiaco told them of a kingdom to the south, where people were so rich that they ate and drank from plates and goblets made of gold, but that the conquerors would need at least a thousand men to defeat the tribes living inland and those on the coast of "the other sea".

Balboa received the unexpected news of a new kingdom – rich in gold – with great interest. Using information given by various friendly caciques, Balboa started his journey across what we now know as the Isthmus of Panama on September 1, 1513, together with 190 Spaniards, a few native guides, and a pack of dogs. Using a small brigantine and ten native canoes, they sailed along the coast and made landfall in cacique Careta's territory. On September 6, the expedition continued, now reinforced with 1,000 of Careta's men, and entered cacique Ponca's land. Ponca had reorganized and attacked, but he was defeated and forced to ally himself with Balboa. After a few days, and with several of Ponca's men, the expedition entered the dense jungle on September 20, and, with some difficulty, arrived four days later in the lands of cacique Torecha, who ruled in the village of Cuarecuá. In this village, a fierce battle took place, during which Balboa's forces defeated Torecha, who was killed by one of Balboa's dogs. Torecha's followers decided to join the expedition. However, the group was by then exhausted and several men were badly wounded, so many decided to stay in Cuarecuá to regain their strength.

The South Sea

The few men who continued the journey with Balboa entered the mountain range along the Chucunaque River the next day. According to information from the natives, one could see the South Sea from the summit of this range. Balboa went ahead and, before noon that day, September 25, he reached the summit and saw, far away in the horizon, the waters of the undiscovered sea. The emotions were such that the others eagerly joined in to show their joy at Balboa's discovery. Andrés de Vera, the expedition's chaplain, intoned the Te Deum, while the men erected stone pyramids, and engraved crosses on the barks of trees with their swords, to mark the place where the discovery of the South Sea was made.

"Silent, upon a peak in Darien."

After the moment of discovery, the expedition descended from the mountain range towards the sea, arriving in the lands of cacique Chiapes, who was defeated after a brief battle and invited to join the expedition. From Chiapes' land, three groups departed in the search for routes to the coast. The group headed by Alonso Martín reached the shoreline two days later.

They took a canoe for a short reconnaissance trip, thus becoming the first Europeans to navigate the Pacific Ocean off the coast of New World. Back in Chiapes' domain, Martín informed Balboa, who, with 26 men, marched towards the coast. Once there, Balboa raised his hands, his sword in one and a standard with the image of the Virgin Mary in the other, walked knee-deep into the ocean, and claimed possession of the new sea and all adjoining lands in the name of the Spanish sovereigns.

After traveling more than 110 km (68 mi), Balboa named the bay where they ended up San Miguel, because they arrived on September 29, the feast day of the archangel Michael. He named the new sea Mar del Sur, since they had traveled south to reach it.

As Waldseemüller's "Admirals Map" was being produced in Strasbourg, with the known New World depicted as accurately as possible, Balboa was confirming one of his two theoretical geographic proposals in the Universalis Cosmographica.

The discovery of the South Sea accelerated everything. This part of the Spanish main was an isthmus. Access to this western ocean hastened the conquistadores conquests, of Montezuma, of the Incas in Peru, and the discovery of prodigious amounts of silver in Bolivia, the translation of immense wealth, across the ocean Magellan was to name the Pacific, from Spain to China. This led to the creation of the Spanish Treasure Fleet, state sponsored piracy and the first era of the globalisation of trade in the context of an emerging mercantile capitalism.

But at what cost, especially to the indigenous populations?

Randy Newman gives an answer, that in two minutes and forty-eight seconds covers the last four hundred years of Western civilization. Balboa discovering the Pacific is mentioned, as is also an episode of staggering cruelty that Balboa was responsible for instigating.

The Great Nations of Europe

Had gathered on the shore

They'd conquered what was behind them

And now they wanted more

So they looked to the mighty ocean

And took to the western sea

The great nations of Europe in the sixteenth century

Hide your wives and daughters

Hide the groceries too

Great nations of Europe coming through

The Grand Canary Islands

First land to which they came

They slaughtered all the canaries

Which gave the land its name

There were natives there called Guanches

Guanches by the score

Bullets, disease, the Portugese, and they weren't there anymore

Now they're gone, they're gone, they're really gone

You've never seen anyone so gone

They're a picture in a museum

Some lines written in a book

But you won't find a live one no matter where you look

Hide your wives and daughters

Hide the groceries too

Great nations of Europe coming through

Columbus sailed for India

Found Salvador instead

He shook hands with some Indians and soon they all were dead

They got TB and typhoid and athlete's foot

Diptheria and the flu

Excuse me - Great nations coming through

Balboa found the pacific

And on the trail one day

He met some friendly Indians

Whom he was told were gay

So he had them torn apart by dogs on religious grounds they say

The great nations of Europe were quite holy in their way

Now they're gone, they're gone, they're really gone

You've never seen anyone so gone

Some bones hidden in a canyon Some paintings in a cave

There's no use trying to save them

There's nothing left to save

Hide your wives and daughters

Hide your sons as well

With the great nations of Europe you never can tell

From where you and I are standing

At the end of a century

Europes have sprung up everyone as even I can see

But there on the horizon as a possiblity

Some bug from out of Africa might come for you and me

Destroying everything in its path

From sea to shining sea

Like the great nations of Europe

In the sixteenth century

The denizens of Hollywood would come up with a more comfortable version of the great nations of Europe and their swashbuckling rivalries played out in glorious Technicolor. The Spanish Main for example.

Dutch sea captain Laurent van Horn is shipwrecked off the coast of the Spanish settlement of Cartagena. After being held and sentenced to death, Van Horn and his crew manage to escape. Five years later, Van Horn has established himself as the mysterious pirate known only by the name of his ship: The Barracuda. After infiltrating the vessel ferrying her to her wedding, they capture Contessa Francisca Alvarado who has been arranged to marry the corrupt governor. Wishing to avoid further bloodshed aboard the escort ship, Francisca offers to marry Van Horn if he will spare the escort, to which he agrees. Over time Francisca and Van Horn become attracted to each other and set out to defeat the villainous governor Don Juan Alvarado and treacherous pirates Du Billar and Capt. Black.