This monument to Queen Victoria stands outside the Queen Victoria Building in Sydney Australia. This sculptural monument to Queen Victoria by the Irish sculptor John Hughes was originally unveiled by King Edward VII in 1904 outside Leinster House in Dublin, the "second city" of the British Empire.

The monumental sculpture, and the portland stone column on which the statue of Queen Victoria sits, was located in the enclosed courtyard of Leinster House on 17 February 1908. At a ceremony with 1000 troops on parade, the Lord Lieutenant declared "we are assembled here to dedicate this noble work of art to the perpetual commemoration of a great personality and a great life."

According to Peter Moore:

The statue shows an effort to portray Victoria Regina as the 'Irish Queen' rather than the 'British Sovereign'. She is seated in a low chair rather than an elaborate throne, allowing the artist to contain the figure within a sphere rather than as a towering pillar. And she wears a simple coronet rather than the royal or imperial crown...Moreover, the statue portrayed her as the Sovereign Head of the Most Illustrious Order of St Patrick, Ireland's order of chivalry dating from 1783. The star on her left breast, and the pendant badge, feature shamrocks, crowned harps, and St Patrick's Cross.

The St Patrick reference probably backfired. It confirmed Ireland's colonial subordination. Round her neck the chain alternates the red and white roses of England.

The statue sat atop a portland stone column, also designed by Hughes, with three sculptural groups to be placed below – "Fame", "Hibernia at Peace" and "Hibernia at War". This last group was also known as "Erin and the Dying Soldier" and referred to the loyalty demonstrated by Irish soldiers in the Boer War. (These associated sculptures from the base of the statue are currently in the collection of Dublin Castle.)

In 1922, 14 years after the statue's installation, Leinster House had become the seat of the Irish parliament, the Oireachtas, and nationalistic sentiment disapproved of having a British queen celebrated in such a location.

The statue had by now been given the nickname "The auld bitch" by Irish writer James Joyce.

In August 1929 The Irish Times reported that discussions were under way to remove the statue “on the basis that its continued presence there is repugnant to national feeling, and that, from an artistic point of view, it disfigures the architectural beauty of the parliamentary buildings.”

As part of the Irish State's move towards declaring a republic, it was removed in July 1948 and replaced with a carpark. It was transported to the Royal Hospital Kilmainham and, along with the associated three sculptural groups, was left in a courtyard. The hospital had been a proposed site for the parliament, and so used as a storage location for property belonging to the National Museum of Ireland. Attempts to send the sculpture to London, Ontario did not succeed as neither the Canadian nor Irish governments wished to pay the cost of transport. In February 1980 the statue was transferred to a yard behind a disused children's reformatory at Daingean, County Offaly.

In the mid-1980s, the iconic Queen Victoria Building in central Sydney was undergoing major renovations after decades of disuse, and appropriate public art was being sought for the entrance. Neil Glasser, Director of Promotions for the company undertaking the renovations (Singapore's Ipoh Gardens Ltd), travelled to several former British colonies in the hope of finding a statue. After a "considerable amount of sleuthing", the statue, sitting in long grass behind the reformatory, was rediscovered and proposed to be moved to Australia.

In order to obtain approval, Glasser contacted John Teahan, the Director of the National Museum of Ireland, and Sydney's Lord Mayor contacted the Irish Ambassador in Canberra. In August 1986 Fine Gael Taoiseach, Garret FitzGerald, authorised that the statue be given to Australia "on loan until recalled". Subsequently, declassified cabinet papers showed that the plan was opposed by the then finance minister John Bruton (later to be Taoiseach), as well as Teahan, on the basis that it represented the work of an Irish artist and;

"...representative of one of the many traditions of Irish history".Despite heavy rain an unveiling ceremony took place on Sunday 20 December 1987 overseen by Eric Neal, Chief Commissioner of Sydney, and Dermot Brangan, first secretary at the Irish embassy to Australia.

The irony of the British Queen being "transported" to Australia by ship was not lost on the Irish media.

To many Irish people Queen Victoria has been known as the "Famine Queen". In the days before the unveiling the embassy and the Daily Telegraph newspaper received anonymous threats of violence and protest about "the propriety of an Irish government giving a statue of Victoria as a gift."

Ireland’s Australian embassy got “threatening and abusive phone calls” over the government’s gift of a statue of Queen Victoria to the city of Sydney, Irish cabinet papers declassified after 30 years have revealed.Perhaps the unveiling of this statue had a capacity to trigger deep, and long standing, feelings of resentment regarding the British Crown. During the years of the Great War many within the Irish diaspora in Australia would resist attempts to introduce conscription by the aforementioned Billy Hughes. Hughes was a strong supporter of Australia's participation in World War I and, after the loss of 28,000 men as casualties (killed, wounded and missing) in July and August 1916, Generals Birdwood and White of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) persuaded Hughes that conscription was necessary if Australia was to sustain its contribution to the war effort.

“In the days preceding the unveiling, you should be aware that the embassy received a number of threatening and abusive phone calls about the propriety of an Irish government giving a statue of Victoria as a gift. The callers demanded to know the name of who was going to represent the Irish government at the ceremony and to warn him/her to stay away,” Brangan said.

However, a two-thirds majority of his party, the Labor Party, which included Roman Catholics and union representatives as well as the Industrialists (Socialists) such as Frank Anstey, were bitterly opposed to this, especially in the wake of what was regarded by many Irish Australians (most of whom were Roman Catholics) as Britain's excessive response to the Easter Rising of 1916.

The Easter Rising as a theme for an interactive computer game!

The Easter Rising was a "watershed moment" for the formation of a modern Irish identity, not so much because of the rebellion against British Rule by a small group of Irish nationalists, but because of the brutal British "imperialist" response.

The Easter Rising, also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week, April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans to end British rule in Ireland and establish an independent Irish Republic while the United Kingdom was heavily engaged in the First World War. It was the most significant uprising in Ireland since the rebellion of 1798, and the first armed action of the Irish revolutionary period.

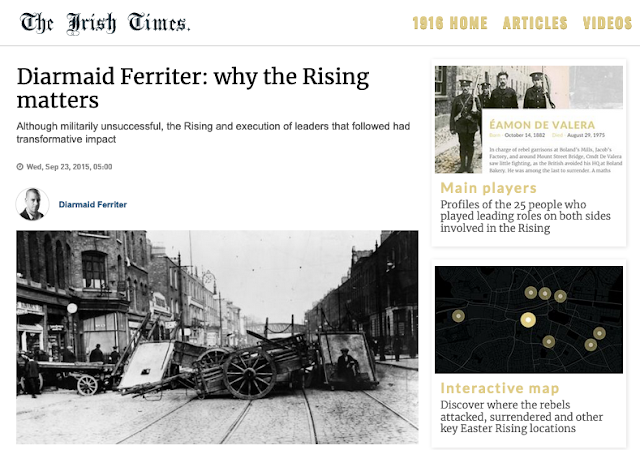

100 years after the Rising the Irish Times published this guide

Wed, Sep 23, 2015, 05:00 Diarmaid Ferriter

The 1916 Rising was the first major revolt against British rule in Ireland since the United Irishmen Rebellion of 1798.Diarmaid Ferriter is professor of modern history in University College Dublin.

During Easter Week 1916, the rebels succeeded in taking over large parts of Dublin city for almost a week, right under the noses of the British empire, then the largest empire in the world. For fewer than 2,000 poorly armed amateur soldiers to take on a country with the political power and military strength of Britain was astonishing.

The Rising matters because, even though the rebels surrendered, it had a huge effect. After the Rising, the British authorities executed the rebel leaders and arrested over 3,500 suspected of involvement. These moves helped convince many people to turn against the British, and seek full independence for Ireland as a separate country.

Some say the people who planned the Rising feared it was the last chance to save a sense of Irishness. At the time of the Rising, 150,000 Irishmen were fighting for Britain in the first World War.

Almost 50 years ago, Garret FitzGerald, who was taoiseach in the 1980s, and whose father had fought in the GPO in 1916, said: “It was planned by men who feared that without a dramatic gesture of this kind, the sense of national identity that had survived all the hazards of the centuries would flicker out ignominiously within their lifetime, leaving Ireland psychologically as well as legally, like Scotland, an integral part of the United Kingdom.”

The Rising has been claimed by many as the founding act of a democratic Irish state. The rebels were determined that decisions affecting Ireland would be taken in Ireland, not in the British parliament in London.

It was also the start of Ireland being seen by some other colonies as a role model for the international struggle against the British empire. Others see the 1916 Rising as a bloody act by a few unelected individuals. The Rising, they say, increased the divisions between Ulster unionists and southern Irish nationalists, and was the start of an era of unnecessary bloodshed and violence. Many of these people say that independence for Ireland could have been achieved peacefully, without the Rising.

The Rising destroyed the Home Rule project. For 40 years, a group of Irish politicians had campaigned for an arrangement that would keep Ireland inside the British empire, but would allow some decisions be taken by Irish members of an Irish home rule parliament.

The Rising killed off this idea. After 1916, people called for recognition of the Republic that had been declared during the Rising.

The rebellion also remains important to some people because of the ideals put forward by the rebels in the Proclamation of 1916. Many of the promises made in the Proclamation – such as equality and social progress – have still not been delivered, they say.

What is indisputable is that 1916 was a hugely significant event that transformed the focus of Irish nationalism, increased divisions and made people more politically aware and active.

The 1916 Rising came to be seen as the first stage in a war of independence that resulted in the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922 and, ultimately, the formal declaration of an Irish Republic in 1949.

The Black (and Tan) Legends

Conscription crisis in Australia

The political mood in Australia amongst the Irish diaspora in 1916 had been shaped by Britain's excessive response to the Easter Rising of 1916, and to an extent comparable with the impact of British imperial policy for the Irish in Ireland too, led to more difficulties in the attempt to extend conscription in Australia for military service in the Great War. In October, Billy Hughes held a national plebiscite for conscription, but it was narrowly defeated. The enabling legislation was the Military Service Referendum Act 1916 and the outcome was advisory only. The narrow defeat (1,087,557 Yes and 1,160,033 No), however, did not deter Hughes, who continued to argue vigorously in favour of conscription. This revealed the deep and bitter split within the Australian community that had existed since before Federation, as well as within the members of his own party.

The Federation of Australia was the process by which the six separate British self-governing colonies of Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia, and Western Australia agreed to unite and form the Commonwealth of Australia, establishing a system of federalism in Australia. Fiji and New Zealand were originally part of this process, but they decided not to join the federation. Following federation, the six colonies that united to form the Commonwealth of Australia as states kept the systems of government (and the bicameral legislatures) that they had developed as separate colonies, but they also agreed to have a federal government that was responsible for matters concerning the whole nation. When the Constitution of Australia came into force, on 1 January 1901, the colonies collectively became states of the Commonwealth of Australia.

British, White, Protestant and anti-Catholic

Soon after Australia became a federation in January 1901, the federal government of Edmund Barton passed the Immigration Restriction Act of 1901, drafted by the man who would become Australia's second Prime Minister, Alfred Deakin. The passage of this bill marked the commencement of the White Australia Policy as Australian federal government policy. Subsequent acts further strengthened the policy up to the start of the Second World War. These policies effectively gave British migrants preference over all others through the first four decades of the 20th century. During the Second World War, Prime Minister John Curtin reinforced the policy, saying:

"This country shall remain forever the home of the descendants of those people who came here in peace in order to establish in the South Seas an outpost of the British race."The nascent Australian labour movement was less than wholly committed in its support for federation. On the one hand, nationalist sentiment was strong within the labour movement and there was much support for the idea of White Australia. On the other hand, labour representatives feared that federation would distract attention from the need for social and industrial reform, and further entrench the power of the conservative forces. The federal conventions included no representatives of organised labour. In fact, the proposed federal constitution was criticised by labour representatives as being too conservative. These representatives wanted to see a federal government with more power to legislate on issues such as wages and prices. They also regarded the proposed senate as much too powerful, with the capacity to block attempts at social and political reform, much as the colonial upper houses were quite openly doing at that time.

Religious factors played a small but not trivial part in disputes over whether federation was desirable or even possible. As a general rule, pro-federation leaders were Protestants, while Catholics' enthusiasm for federation was much weaker, not least because Sir Henry Parkes, the "Father of Federation", had been militantly anti-Catholic for decades, and because the labour movement was disproportionately Catholic in its membership.

Conscription had been in place since the 1910 Defence Act, but only in the defence of the nation. Hughes was seeking via a referendum to change the wording in the act to include "overseas", and therefore enable Australia to have a role in the ongoing World War. A referendum was not necessary but Hughes felt that in light of the seriousness of the situation, a vote of "Yes" from the people would give him a mandate to bypass the Senate. On 15 September 1916 the NSW executive of the Political Labour League, Frank Tudor expelled Hughes from the Labor Party, after Hughes and 24 others had already walked out to the sound of Hughes's finest political cry "Let those who think like me, follow me." Hughes took with him almost all of the Parliamentary talent, leaving behind the Industrialists and Unionists, thus marking the end of the first era in Labor's history. Years later, Hughes said, "I did not leave the Labor Party, The party left me."

In Dublin, and in Ireland, following the Easter Rising, life went on . . .

However, nothing would be the same again!

At first, many Dubliners were bewildered by the outbreak of the Rising. James Stephens, who was in Dublin during the week, thought:

"None of these people were prepared for Insurrection. The thing had been sprung on them so suddenly they were unable to take sides."There was great hostility towards the Volunteers in some parts of the city. Historian Keith Jeffery noted that most of the opposition came from people whose relatives were in the British Army and who depended on their Army allowances. Those most openly hostile to the Volunteers were the "separation women" (so-called because they were paid "separation money" by the British government), whose husbands and sons were fighting in the British Army in the First World War. There was also hostility from unionists. Supporters of the Irish Parliamentary Party also felt the rebellion was a betrayal of their party. When occupying positions in the South Dublin Union and Jacob's factory, the rebels got involved in physical confrontations with civilians who tried to tear down the rebel barricades and prevent them taking over buildings. The Volunteers shot and clubbed a number of civilians who assaulted them or tried to dismantle their barricades.

That the Rising resulted in a great deal of death and destruction, as well as disrupting food supplies, also contributed to the antagonism toward the rebels. After the surrender, the Volunteers were hissed at, pelted with refuse, and denounced as "murderers" and "starvers of the people". Volunteer Robert Holland for example remembered being "subjected to very ugly remarks and cat-calls from the poorer classes" as they marched to surrender. He also reported being abused by people he knew as he was marched through the Kilmainham area into captivity and said the British troops saved them from being manhandled by the crowd.

However, some Dubliners expressed support for the rebels. Canadian journalist and writer Frederick Arthur McKenzie wrote that in poorer areas, "there was a vast amount of sympathy with the rebels, particularly after the rebels were defeated". He wrote of crowds cheering a column of rebel prisoners as it passed, with one woman remarking "Shure, we cheer them. Why shouldn't we? Aren't they our own flesh and blood?". At Boland's Mill, the defeated rebels were met with a large crowd, "many weeping and expressing sympathy and sorrow, all of them friendly and kind". Other onlookers were sympathetic but watched in silence. Christopher M. Kennedy notes that "those who sympathised with the rebels would, out of fear for their own safety, keep their opinions to themselves". Áine Ceannt witnessed British soldiers arresting a woman who cheered the captured rebels. An RIC District Inspector's report stated: "Martial law, of course, prevents any expression of it; but a strong undercurrent of disloyalty exists". Thomas Johnson, the Labour leader, thought there was, "no sign of sympathy for the rebels, but general admiration for their courage and strategy".

The aftermath of the Rising, and in particular the British reaction to it, helped sway a large section of Irish nationalist opinion away from hostility or ambivalence and towards support for the rebels of Easter 1916. Dublin businessman and Quaker James G. Douglas, for example, hitherto a Home Ruler, wrote that his political outlook changed radically during the course of the Rising because of the British military occupation of the city and that he became convinced that parliamentary methods would not be enough to remove the British presence.

After the surrender the country remained under martial law. About 3,500 people were taken prisoner by the British, many of whom had played no part in the Rising, and 1,800 of them were sent to internment camps or prisons in Britain. Most of the leaders of the Rising were executed following courts-martial. The Rising brought physical force republicanism back to the forefront of Irish politics, which for nearly 50 years had been dominated by constitutional nationalism. It, and the British reaction to it, led to increased popular support for Irish independence.

After the Rising, claims of atrocities carried out by British troops began to emerge. Although they did not receive as much attention as the executions, they sparked outrage among the Irish public and were raised by Irish MPs in Parliament.

One incident was the 'Portobello killings'. On Tuesday 25 April, Dubliner Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, a pacifist nationalist activist, had been arrested by British soldiers. Captain John Bowen-Colthurst then took him with a British raiding party as a hostage and human shield. On Rathmines Road he stopped a boy named James Coade, whom he shot dead. His troops then destroyed a tobacconist's shop with grenades and seized journalists Thomas Dickson and Patrick MacIntyre. The next morning, Colthurst had Skeffington and the two journalists shot by firing squad in Portobello Barracks. The bodies were then buried there. Later that day he shot a Labour Party councillor, Richard O'Carroll. When Major Sir Francis Vane learned of the killings he telephoned his superiors in Dublin Castle, but no action was taken. Vane informed Herbert Kitchener, who told General Maxwell to arrest Colthurst, but Maxwell refused. Colthurst was eventually arrested and court-martialled in June. He was found guilty of murder but insane, and detained for twenty months at Broadmoor. Public and political pressure led to a public inquiry, which reached similar conclusions. Major Vane was discharged "owing to his action in the Skeffington murder case".

The other incident was the 'North King Street massacre'. On the night of 28–29 April, British soldiers of the South Staffordshire Regiment, under Colonel Henry Taylor, had burst into houses on North King Street and killed 15 male civilians whom they accused of being rebels. The soldiers shot or bayoneted the victims, then secretly buried some of them in cellars or back yards after robbing them. The area saw some of the fiercest fighting of the Rising and the British had taken heavy casualties for little gain. General Maxwell attempted to excuse the killings and argued that the rebels were ultimately responsible. He claimed that "the rebels wore no uniform" and that the people of North King Street were rebel sympathisers. Maxwell concluded that such incidents "are absolutely unavoidable in such a business as this" and that "Under the circumstance the troops [...] behaved with the greatest restraint". A private brief, prepared for the Prime Minister, said the soldiers "had orders not to take any prisoners" but took it to mean they were to shoot any suspected rebel. The City Coroner's inquest found that soldiers had killed "unarmed and unoffending" residents. The military court of inquiry ruled that no specific soldiers could be held responsible, and no action was taken.

These killings, and the British response to them, helped sway Irish public opinion against the British.

Under Regulation 14B of the Defence of the Realm Act 1914 1,836 men were interned at internment camps and prisons in England and Wales.[134] Many of them, like Arthur Griffith, had little or nothing to do with the Rising. Camps such as Frongoch internment camp became "Universities of Revolution" where future leaders including Michael Collins, Terence McSwiney and J. J. O'Connell began to plan the coming struggle for independence.

Sir Roger Casement was tried in London for high treason and hanged at Pentonville Prison on 3 August. Roger David Casement (known as Sir Roger Casement, CMG, between 1911 and 1916), was a diplomat and Irish nationalist. He worked for the British Foreign Office as a diplomat and later became a humanitarian activist, poet and Easter Rising leader.

He has been described as the;

"father of twentieth-century human rights investigations".

He was honoured in 1905 for the Casement Report on the Congo and knighted in 1911 for his important investigations of human rights abuses in Peru. In Africa as a young man, Casement first worked for commercial interests before joining the British Colonial Service. In 1891 he was appointed as a British consul, a profession he followed for more than 20 years. Influenced by the Boer War and his investigation into colonial atrocities against indigenous peoples, Casement grew to distrust imperialism. After retiring from consular service in 1913, he became more involved with Irish republicanism and other separatist movements. During World War I he made efforts to gain German military aid for the 1916 Easter Rising that sought to gain Irish independence.

Casement's Black Diaries

Casement was arrested, convicted and executed for high treason. He was stripped of his knighthood and other honours. Before the trial, the British government circulated excerpts said to be from his private journals, known as the Black Diaries, which detailed homosexual activities. Given prevailing views and existing laws on homosexuality, this material undermined support for clemency for Casement. Debates have continued about these diaries: a handwriting comparison study in 2002 concluded Casement had written the diaries, but this was still contested by some.

At Casement's highly publicised trial for high treason, the prosecution had trouble arguing its case. Casement's crimes had been carried out in Germany and the Treason Act 1351 seemed to apply only to activities carried out on English (or arguably British) soil. A close reading of the Act allowed for a broader interpretation: the court decided that a comma should be read in the unpunctuated original Norman-French text, crucially altering the sense so that "in the realm or elsewhere" referred to where acts were done and not just to where the "King's enemies" might be.

Afterwards, Casement himself wrote that he was to be "hanged on a comma", leading to the well-used epigram.

The Trial of Roger Casement, 1916, painted by John Lavery

Fintan O’Toole writes in the Irish Times

Sat, Mar 26, 2016

After the Easter Rising, in the summer of 1916, the most famous Irishman in the world tried to save the last of the rebel leaders from execution. George Bernard Shaw was highly controversial, and his scepticism about the first World War had outraged mainstream British opinion. But he was still regarded as the world’s most important playwright. And now he sat down to draft a dramatic monologue for a very specific actor. It was to be performed for a very small and select audience. And it had a precise purpose: to save a life.

The actor he envisaged for the part was Roger Casement, who was about to go on trial in London for the capital crime of high treason, for seeking to import arms from Germany to Ireland in preparation for a rising.

Shaw attempted, in full seriousness, to get Casement to perform a script for the jury that would try him. The dramatic stakes could not have been higher: Casement would literally perform to save his life. The playwright’s proven capacity to make an English audience feel and think what it did not want to feel or think would, through the voice of the accused, force an English jury to acquit an Irish traitor.

Shaw did not think that Casement was right to forge an alliance with Germany. He was even more deeply opposed to what he saw as Prussian militarism than he was to the English ruling class. He would write, in a letter of June 1917, that the Germans, if victorious, would show “as ruthless a contempt for Irish as for Polish nationality”. But he did believe that Casement, as an Irishman, owed no allegiance to the British Empire and had the right to do what he sincerely believed was best for his own country, Ireland.

For all that he spent most of his career in England, Shaw’s profound understanding of Irish nationalism was revealed in the wake of the 1916 Rising, when he was the only public figure of any importance to predict that the execution of the leaders would transform Irish public opinion.

While the executions were still in progress, and while Irish newspapers and mainstream nationalists were still denouncing the rebellion as monstrous, Shaw, in the London Daily News of May 10th, 1916, wrote that the rebels had merely done what an English patriot would do were the Germans to win the war and occupy England.

Executing such a rebel, he argued, would make him “a martyr and a hero, even though the day before the rising he may have been only a minor poet”.

Shaw was personally sceptical about the value of martyrdom. In his play The Devil’s Disciple Gen Burgoyne does not really want to hang the apparent rebel Dick Dudgeon: “It is making too much of the fellow to execute him. Martyrdom, sir, is what these people like: it is the only way in which a man can become famous without ability.”

But Shaw knew his Irish history. He presciently warned the British that “the shot Irishmen will now take their places beside Emmet and the Manchester martyrs in Ireland, and beside the heroes of Poland and Serbia and Belgium in Europe, and nothing in heaven or on earth can prevent it.”

And it was this line of argument that Shaw tried to get Casement to put to the jury at his treason trial.

Beatrice Webb, the economist and historian with whom Shaw had co-founded the London School of Economics, recorded in her diary for May 21st, 1916, a meeting between herself, Shaw and Casement’s great friend Alice Stopford Green. As she wrote in astonishment and irritation: “Shaw wants to compel Casement and Casement’s friends to ‘produce’ the defence as a national dramatic event.” Webb was appalled: “His conceit is monstrous.”

But Shaw was right: Casement’s trial, following on from the executions of the other leaders of the Rising, was indeed a national dramatic event. What concerned Shaw was what kind of drama it would be.

There was a tragic template for these shows, in which the climax was an inevitable execution. Shaw brought to bear on this template his contrary intelligence, seeking to infuse it with his own dramaturgy in which the inevitable almost never happens. He wanted to save Casement from martyrdom. As Shaw later explained, Casement’s trial was set to play out in an entirely predictable pattern: “I knew that the conventional legal defence which his lawyers were certain to advise would infallibly hang him after eliciting compliments from the Bench for its ability and eloquence. The facts were undeniable; but learned counsel would refuse to admit them and would cross examine the Crown witnesses at the utmost possible length so as to give plenty of value for their fees.

“The Lord Chief Justice would compliment; the jury would admire; and everybody except the prisoner would be perfectly happy in the obvious certainty that the facts were the facts, the witnesses unshakeable, and a verdict of guilty certain.”

In this familiar scenario Casement would make his heroic speech from the dock after his fate had been sealed by that verdict. In Shaw’s drama, to the contrary, he would conduct his own defence and speak to the jury before it had condemned him. In the play that Shaw wrote for his enactment Casement would contest none of the facts about his dealings with Germany. Instead he would, in the Shavian manner, turn treason inside out and reveal its opposite: patriotism and loyalty.

Casement would plead simply that he could not be a traitor because he was not English: “If you persist in treating me as an Englishman, you bind yourself thereby to hang me as a traitor before the eyes of the world.

“Now as a simple matter of fact, I am neither an Englishman nor a traitor: I am an Irishman, captured in a fair attempt to achieve the independence of my country; and you can no more deprive me of the honours of that position, or destroy the effects of my effort, than the abominable cruelties inflicted six hundred years ago on William Wallace in this city when he met a precisely similar indictment with a precisely similar reply, have prevented that brave and honourable Scot from becoming the national hero of his country.”

In this performance there is no pleading: “I ask for no mercy, no pardon, no pity.” In fact Shaw’s Casement gently teases his audience of jurors. They may, he suggests, be tempted to hang him not as a traitor but as a fool, because the Rising was a quixotic failure. But quixotic failures were the order of the day in the Great War: “Will you understand me when I say that those . . . days of splendid fighting against desperate odds in the streets of Dublin have given back Ireland her self-respect? We were beaten, indeed never had a dog’s chance of victory; but you also were beaten in a no less rash and desperate enterprise in Gallipoli. Are you ashamed of it? Did your hearts burn any the less . . . because you were at last driven into the sea by the Turks? Well, what you feel about the fight in Gallipoli, Irishmen feel all over the world about the fight in Dublin.”

The brilliance of Shaw’s dramatic provocation of the jury lies in the way it frames and subverts their power. The jurors had absolute power to have Casement hanged for treason. But Shaw’s Casement subtly suggests that this is not power at all, because if they set out to hang a traitor they will succeed merely in creating a martyr: “I am not trying to shirk the British scaffold: it is the altar on which Irish saints have been canonized for centuries.”

Shaw as Casement is certain of his posthumous status: “My neck is at your mercy if it amuses you to break it; my honour and my reputation are beyond your reach.”

On the contrary, therefore, the only real power the jurors have is to acquit Casement of treason, thereby depriving him of Irish sainthood. It is a perfect Shavian paradox.

Shaw’s play for Casement was not performed. Casement’s lawyers persuaded him to adopt a conventional defence, contesting the facts and making his speech only after he had been condemned.

Casement, while awaiting his execution, regretted that he had not performed Shaw’s “national drama”.

As for Shaw, like any artist he wasted nothing. His last great play, Saint Joan, is, at heart, his considered response to the Rising and in particular to Casement’s martyrdom.

Joan’s unbreakable will to sweep the English out of France, her trial and her ultimate decision to choose death over imprisonment all echo Casement’s real drama. Joan, too, returns after death as an image and an inspiration: nothing in heaven and earth can prevent her spiritual and temporal triumph. Shaw’s “national drama” may be disguised as French, but it is deeply Irish.

Easter, 1916 is a poem by W. B. Yeats describing the poet's torn emotions regarding the events of the Easter Rising staged in Ireland against British rule on Easter Monday, April 24, 1916. The uprising was unsuccessful, and most of the Irish republican leaders involved were executed for treason. The poem was written between May and September 1916, but first published in 1921 in the collection Michael Robartes and the Dancer.

Even though a committed nationalist, Yeats usually rejected violence as a means to secure Irish independence, and as a result had strained relations with some of the figures who eventually led the uprising. The deaths of these revolutionary figures at the hands of the British, however, were as much a shock to Yeats as they were to ordinary Irish people at the time, who did not expect the events to take such a bad turn so soon. Yeats was working through his feelings about the revolutionary movement in this poem, and the insistent refrain that "a terrible beauty is born" turned out to be prescient, as the execution of the leaders of the Easter Rising by the British had the opposite effect to that intended. The killings led to a reinvigoration of the Irish Republican movement rather than its dissipation.

The poem ends with these lines, an augury of what was to come . . .

And what if excess of loveW. B. Yeats

Bewildered them till they died?

I write it out in a verse—

MacDonagh and MacBride

And Connolly and Pearse

Now and in time to be,

Wherever green is worn,

Are changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

Conscription Crisis 1918 in Ireland

The Conscription Crisis of 1918 stemmed from a move by the British government to impose conscription (military draft) in Ireland in April 1918 during the First World War. Vigorous opposition was led by trade unions, Irish nationalist parties and Roman Catholic bishops and priests. A conscription law was passed but was never put in effect; no one in Ireland was drafted into the British Army.

By June 1918 it had become apparent to most observers in Britain and Ireland that following American entry into the war the tide of war had changed in favour of the Allied armies in Europe, and by 20 June the Government had dropped its conscription and home rule plans, given the lack of agreement of the Irish Convention. However the legacy of the crisis remained.

Completely ineffectual as a means to bolster battalions in France, the events surrounding the Conscription Crisis were disastrous for the Dublin Castle authorities, and for the more moderate nationalist parties in Ireland. The delay in finding a resolution to the home rule issue, partly caused by the war, and exaggerated by the Conscription Crisis in Ireland, all increased support for Sinn Féin.

Sinn Féin's association, in the public perception at least, with the 1916 Easter Rising and the anti-conscription movement, directly and indirectly led on to their landslide victory over and effective elimination of the Irish Parliamentary Party, the formation of the first Dáil Éireann and in turn to the outbreak of the Anglo-Irish War in 1919.

This opposition also led in part to Sinn Féin being ignored by the subsequent victors at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, despite its electoral success. It appointed representatives who moved to Paris and several times requested a place at the conference, with recognition of the Irish Republic, but never received a reply.

The crisis was also a watershed in Ulster Unionism's relations with Nationalist Ireland, as expressed by Unionist leader James Craig: "for Ulster Unionists the conscription crisis was the final confirmation that the aspirations of Nationalists and Unionists were unrecompatible.

The conscription proposal, and the backlash that followed, galvanised support for political parties which advocated Irish separatism and influenced events in the lead-up to the Irish War of Independence.

Growing support amongst the Irish populace for the republican Sinn Féin political party saw it win 73 out of 105 seats in the Irish general election, 1918. On 21 January 1919, Sinn Féin established themselves as the First Dáil, which then declared an independent Irish Republic. They also declared the Irish Republican Army (IRA) the official army of the state, which in the same month began the Irish War of Independence. The main targets of the IRA offensive were the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and the British Army in Ireland.

In September 1919 David Lloyd George, the British Prime Minister, outlawed the Dáil and augmented the British Army presence in Ireland, starting work on the next Home Rule Act.

A Black and Tan in Dublin, smoking and carrying a Lewis gun, February 1921

In January 1920, the British government started advertising in British cities for men willing to "face a rough and dangerous task", helping to boost the ranks of the RIC in policing an increasingly anti-British Ireland. There was no shortage of recruits, many of them unemployed First World War army veterans, and by November 1921 about 9,500 men had joined. This sudden influx of men led to a shortage of RIC uniforms, and the new recruits were issued with khaki army uniforms (usually only trousers) and dark green RIC or blue British police surplus tunics, caps and belts. These uniforms differentiated them from the British Army and the regular RIC, and gave rise to the force's nickname: Christopher O'Sullivan wrote in the Limerick Echo on 25 March 1920 that, meeting a group of recruits on a train at Limerick Junction, the attire of one reminded him of the Scarteen Hunt, whose "Black and Tans" nickname derived from the colouration of its Kerry Beagles.

Ennis comedian Mike Nono elaborated the joke in Limerick's Theatre Royal, and the nickname soon took hold, persisting even after the men received full RIC uniforms. The popular Irish claim made at the time that most of the men serving in the Black and Tans had criminal records and had been recruited straight from British prisons is incorrect, as a criminal record would disqualify one from working as a policeman. The vast majority of the men serving in the Black and Tans were unemployed veterans of the First World War who were having trouble finding jobs, and for most of them it was economic reasons that drove them to join the Temporary Constables.

The new recruits received three months' hurried training, and were rapidly posted to RIC barracks, mostly in rural County Dublin, Munster and eastern Connacht. The first men arrived on 25 March 1920. The British government also raised another unit, the Auxiliary Division of the constabulary, known as the Auxiliaries or Auxies, consisting of ex-army officers. The Black and Tans aided the Auxiliaries in the British government's attempts to break both the IRA and the Dáil. The Blacks and Tans were meant to back up the RIC in the struggle against the IRA, playing a defensive-reactive role whereas the role of the "Auxies" were those of heavily armed, mobile units meant for offensive operations in the Irish countryside intended to hunt down and destroy IRA units. At least part of the infamy of the Blacks and Tans is undeserved as many of the war crimes attributed to the Blacks and Tans were actually the work of the "Auxies".

The Black and Tans were not subject to strict discipline in their first months and, as a result, their deaths at the hands of the IRA in 1920 were often repaid with arbitrary reprisals against the civilian population. In the summer of 1920, the Black and Tans burned and sacked many small towns and villages in Ireland, beginning with Tuam in County Galway in July 1920 and also including Trim, Balbriggan, Knockcroghery, Thurles and Templemore amongst many others. In November 1920, the Tans "besieged" Tralee in revenge for the IRA abduction and killing of two local RIC men. They closed all the businesses in the town, let no food in for a week and shot dead three local civilians. On 14 November, the Tans were suspected of abducting and murdering a Roman Catholic priest, Father Michael Griffin, in Galway. His body was found in a bog in Barna a week later. From October 1920 to July 1921, the Galway region was "remarkable in many ways", most notably the level of police brutality towards suspected IRA members, which was far above the norm in the rest of Ireland.

On the night of 11 December 1920, they sacked Cork, destroying a large part of the city centre.

In January 1921, the British Labour Commission produced a report on the situation in Ireland which was highly critical of the government's security policy. It said the government, in forming the Black and Tans, had;

"liberated forces which it is not at present able to dominate".However, since 29 December 1920, the British government had sanctioned "official reprisals" in Ireland – usually meaning burning property of IRA men and their suspected sympathisers. Taken together with an increased emphasis on discipline in the RIC, this helped to curb the random atrocities the Black and Tans committed since March 1920 for the remainder of the war, if only because reprisals were now directed from above rather than being the result of a spontaneous desire for revenge.

The actions of the Black and Tans alienated public opinion in both Ireland and Great Britain. Their violent tactics encouraged the Irish public to increase their covert support of the IRA, while the British public pressed for a move towards a peaceful resolution. Edward Wood MP, better known as the future Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax, rejected force and urged the British government to make an offer to the Irish "conceived on the most generous lines". Sir John Simon MP, another future Foreign Secretary, was also horrified at the tactics being used. Lionel Curtis, writing in the imperialist journal The Round Table, wrote: "If the British Commonwealth can only be preserved by such means, it would become a negation of the principle for which it has stood". The King, senior Anglican bishops, MPs from the Liberal and Labour parties, Oswald Mosley, Jan Smuts, the Trades Union Congress and parts of the press were increasingly critical of the actions of the Black and Tans.

Mahatma Gandhi said of the British peace offer:

"It is not fear of losing more lives that has compelled a reluctant offer from England but it is the shame of any further imposition of agony upon a people that loves liberty above everything else".Lawrence James, The Rise and Fall of the British Empire (Abacus, 1998), p. 384.